Before Supreme became a global fashion juggernaut—before the box logo turned into a billion-dollar icon—it was just a gritty downtown skate shop, run by kids who didn’t care if you belonged. In Empire Skate, ESPN’s newest 30 for 30 documentary, director Josh Swade revisits the chaotic roots of the brand that redefined streetwear, revealing a raw and human story built not on hype, but on community, rebellion, and a bit of beautiful chaos.

Before the hype, there was Lafayette

To the untrained eye, Supreme began as a logo—a red box, white letters, a whisper of exclusivity turned global phenomenon. But Empire Skate pulls back the curtain, tracing Supreme’s real origin: a cramped storefront on Lafayette Street in 1994, at the time a desolate pocket of Manhattan. The store’s founder, James Jebbia, wasn’t aiming for empire. He simply opened a skate shop—a place for a handful of punk-minded kids to gather, hang out, and maybe sell a T-shirt or two.

That first store wasn’t friendly. The staff, mostly skaters like Peter Bici, Mike Hernandez, and Gio Estevez, were just as likely to tell a customer to leave as they were to sell them a board. It wasn’t performance—it was culture. The real kind, not the algorithmic kind. As Swade says in the film, “There was a kind of not giving a fuck that was all part of the magic.” Supreme wasn’t born from a marketing strategy; it was born from real kids who had nowhere else to be and nothing else to lose.

This was New York in the early ’90s—edgy, grimy, deeply alive. The kind of place where a skate shop doubling as a clubhouse made perfect sense. And when several of the kids orbiting Supreme were cast in Larry Clark’s cult film Kids, the gritty subculture they represented suddenly had a spotlight—and Supreme, unwittingly, had a myth.

Subculture as foundation, not brand strategy

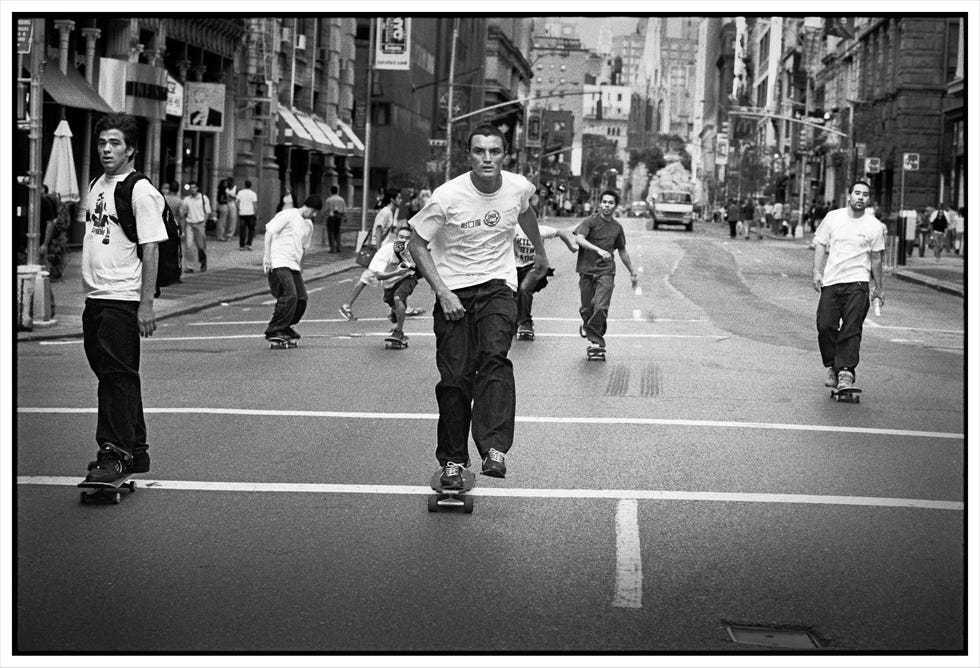

Empire Skate makes clear what streetwear historians and early Supreme heads have always known: the brand’s soul lies in the kids who made it matter, not in the collectors who came later. Back then, fashion was what you wore because it worked, not because it trended. The shop was, as journalist Rachel Tashjian notes in the film, “menacingly New York.” Loud music, beer in the back, tricks on the pavement out front—it was an anti-store that somehow became the center of cool.

Swade draws a smart parallel to Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood’s SEX shop in London, which birthed the Sex Pistols and an entire punk aesthetic. Like SEX, Supreme was less retail outlet and more cultural nucleus—a meeting ground where a generation’s outlook, sound, and style coalesced. “Without the SEX shop,” Swade says, “we don’t have a window into punk. And without Supreme, we wouldn’t understand skate culture’s influence on modern fashion.”

Supreme’s early community wasn’t curated; it was discovered. A scene formed not because anyone was trying to go viral, but because they needed a place to belong. And it’s that authenticity—chaotic, unfiltered, and often unwelcoming—that gave Supreme its rare staying power.

A story told from the pavement

Swade’s decision not to center James Jebbia in the film feels deliberate and effective. “This really wasn’t about what the master plan was from a business perspective,” he explains. “It was always meant to be from the pavement level.” While Jebbia’s genius—quiet, calculated, and understated—inevitably threads through the narrative, Empire Skate isn’t a startup success story. It’s a human one.

What emerges is a portrait of a group of kids who were essentially surviving—finding purpose through skating, camaraderie, and the unlikely sanctuary of a skate shop turned sanctuary. The emotional resonance of the film becomes especially clear when some of those original Supreme crew members, like Bici and Hernandez, talk about their later work as firefighters. “They talked about having run through their city then,” Swade says, “and now they serve their city. It really is touching.”

That full-circle moment underlines the real message of Empire Skate: behind every logo is a story. Behind every streetwear boom is a street. And behind Supreme is a crew of misfit kids who just wanted to skate and be left alone.

A different kind of legacy

Today, the blocks around Lafayette Street are filled not with skaters but with curated boutiques and matcha cafés. Supreme has stores around the world and collaborations with Louis Vuitton. A hoodie can resell for five figures. It’s hard to imagine the original shop—loud, smelly, and standoffish—existing in this reality. But Empire Skate doesn’t mourn that transformation. Instead, it captures what can never be replicated: a moment in time when culture was built by hand, not hashtags.

Swade’s film is a reminder that the coolest things often start on the fringes. Supreme’s brilliance wasn’t about exclusivity—it was about community, about rebellion, about not caring if you were watching. And though the brand has become a global phenomenon, Empire Skate insists its essence still belongs to the kids who built it—one grind, one beer, one “fuck off” at a time.

As the documentary closes, it leaves you with a sense of nostalgia, yes—but also of respect. Because even if Supreme has changed, Empire Skate ensures we never forget what it was, and why that matters.