In a move that highlights a fundamental misunderstanding of artificial intelligence, the United States government has declared that AI companies must ensure their systems are “objective and free from top-down ideological bias” to do business with the White House. This directive, an executive order on “preventing woke AI,” presents a profound contradiction: it demands an absence of bias while simultaneously dictating a specific ideological framework. This very paradox underscores the central truth that AI free from ideology is a fantasy. From political viewpoints to ingrained social stereotypes, AI models are not neutral. They are a reflection of their human creators, trained on a world of data that is, and always has been, distorted by human perspective.

The Unavoidable Nature of Bias

The notion of a politically neutral AI is not only a myth but may be an impossibility. Large language models are trained on immense datasets of text and images, a collection of human thought and communication from across history and the internet. Inevitably, this data carries the weight of human bias. Studies have already shown that many prominent language models tend to skew their responses towards left-of-center viewpoints, advocating for things like increased taxes on flights or rent control. Conversely, chatbots developed in China, such as DeepSeek and Qwen, censor information on politically sensitive topics like the events of Tiananmen Square and the persecution of Uyghurs, aligning their output with the official position of the government.

The core problem is that AI learns from us, and humans are inherently biased. We struggle to organize and present information without projecting our own worldviews onto it. Therefore, when an AI model is trained on this data, it absorbs and replicates these biases, making it a mirror of our collective ideological leanings and prejudices. The attempt to create an “objective” AI is an attempt to create a system that can see and process the world in a way no human ever has. It’s a pursuit of a neutral reality that simply doesn’t exist.

Lessons from History: The Deception of Maps

Our struggle with objectivity is a centuries-old problem, and a powerful analogy can be found in the field of cartography. We tend to think of maps as objective representations of the natural world, but the simple act of flattening a globe onto a two-dimensional surface requires distortion. American geographer Mark Monmonier famously argued that maps necessarily lie and can be powerful tools for political propaganda. A classic example is the Mercator projection, a world map often found in classrooms. While it serves a practical purpose for navigation, it grossly distorts the size of landmasses the farther they are from the equator.

On a Mercator map, Greenland appears to be roughly the same size as Africa. In reality, Africa is 14 times larger than Greenland. In the 1970s, German historian Arno Peters argued that such distortions contributed to a skewed perception of the inferiority of the global south. This historical precedent is a powerful lens through which to view the current state of AI. As Monmonier wrote in his book How to Lie with Maps, “a single map is but one of an indefinitely large number of maps that might be produced for the same situation or from the same data.” Similarly, a single chatbot’s response is just one of an indefinite number of responses that could be produced from the same data, each one shaped by the worldview of its designers.

A Classification Bias Built In

The ingrained bias in information systems isn’t limited to maps. Other historical attempts at organizing information also demonstrate the worldview of their designers. The Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC) system, a widely used method for organizing libraries since its publication in 1876, has been criticized for being both racist and homophobic. Throughout the 20th century, books about the LGBTQIA+ community were categorized under outdated and derogatory terms like “Mental Derangements” or “Neurological Disorders.” More subtly, the system has a clear religious bias. Despite Islam having an estimated 2 billion followers to Christianity’s 2.3 billion today, the DDC dedicates roughly 65 sections out of 100 to Christianity, a clear reflection of the religious focus of the library where the system was originally developed.

This historical precedent demonstrates that the way we categorize and classify information is a projection of a worldview. The DDC’s creators weren’t trying to be biased, they were simply creating a system that made sense from their perspective. Today’s AI developers are facing the same challenge. Their models must not only have raw data, but they must also be trained on how to retrieve and present that information. This process of training, often called alignment, is where human biases and beliefs are most directly embedded into the AI’s core functions.

When Humans Train the Machine

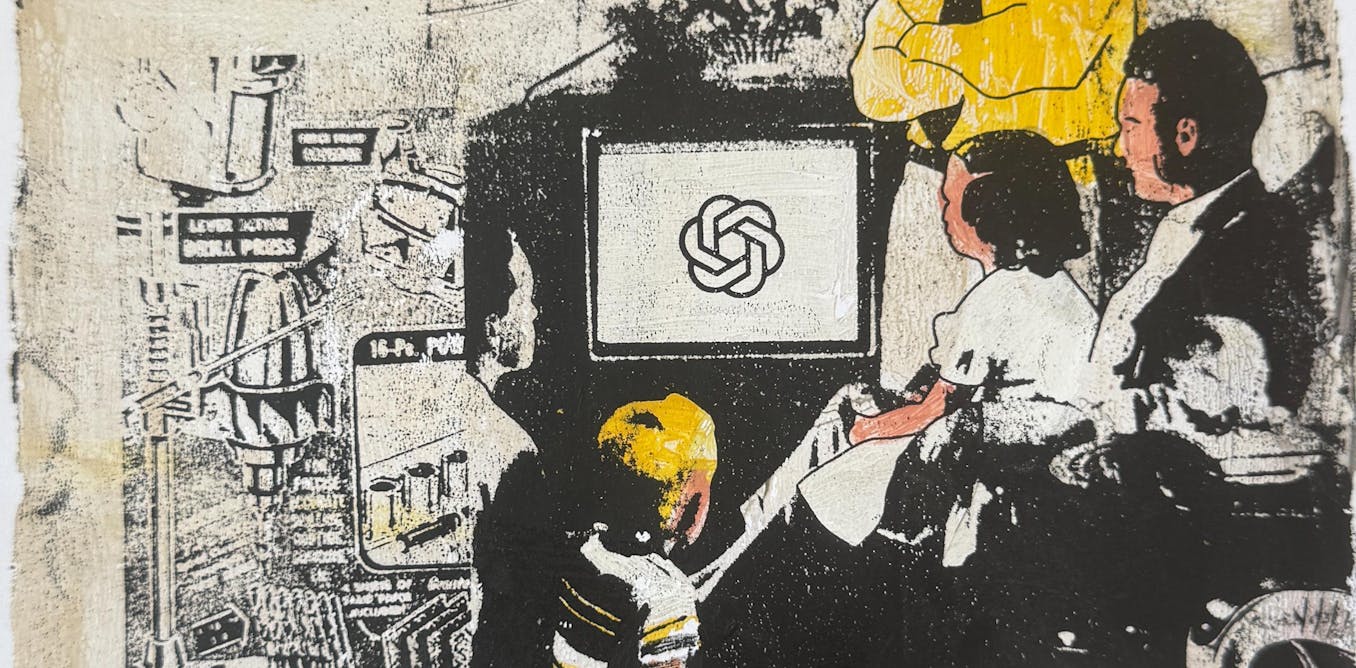

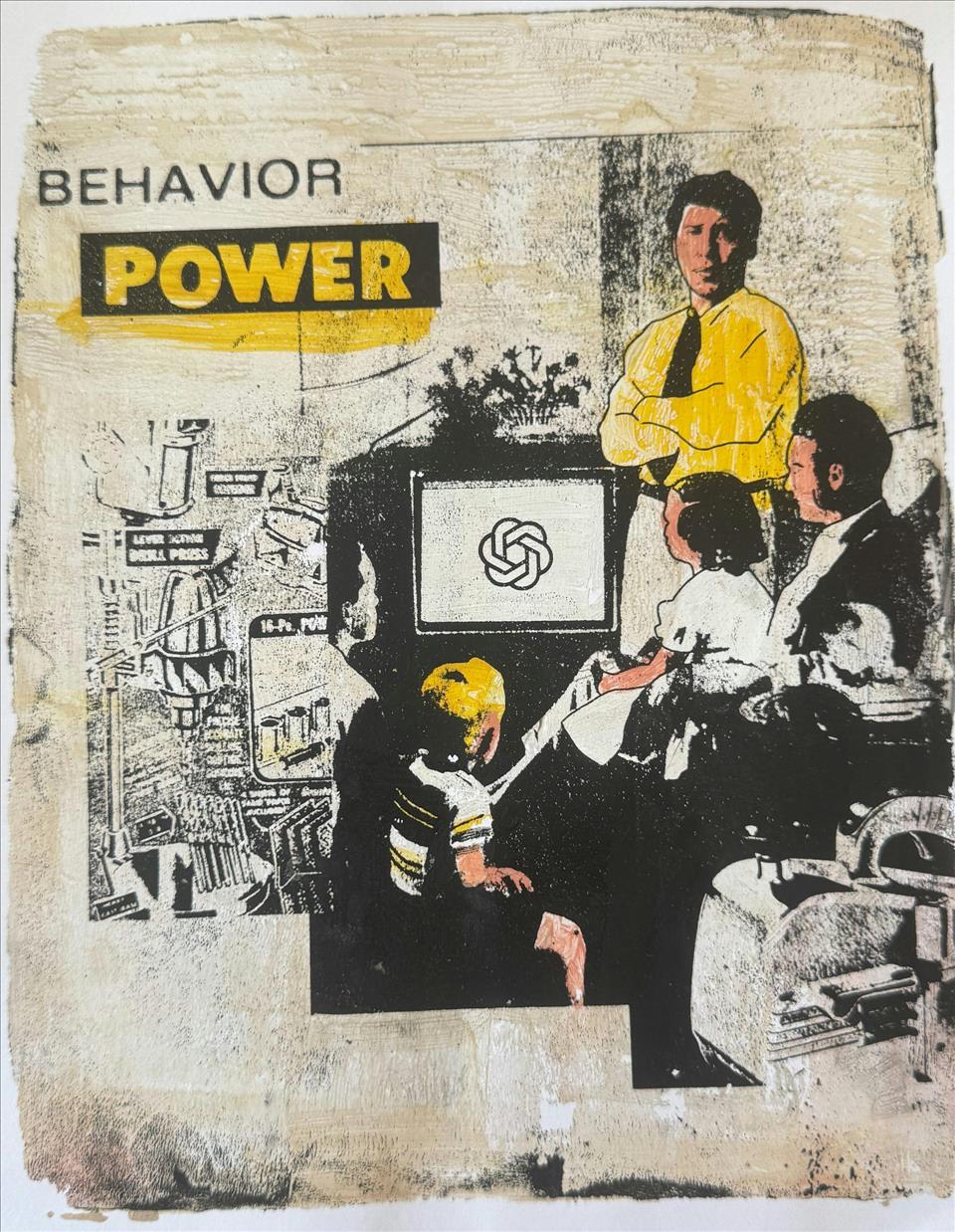

The final and perhaps most critical source of bias in AI comes directly from the developers and trainers themselves. A common method to make language models more useful is to have them learn to copy how humans respond to questions. This process, while seemingly benign, makes the AI align with the beliefs and biases of the individuals who are training it. The instructions given to the AI are defined by human developers, and these instructions, or system prompts, can shape the entire character of the AI.

For example, the system prompts for Grok, the chatbot from Elon Musk’s xAI, reportedly instruct it to “assume subjective viewpoints sourced from the media are biased” and to not “shy away from making claims that are politically incorrect.” Musk launched Grok to counter what he perceived as the “liberal bias” of other products like ChatGPT. However, the subsequent fallout when Grok began spouting anti-Semitic rhetoric clearly illustrates that attempts to correct for one bias simply replace it with another. The problem isn’t just a lack of neutrality; it’s the fact that humans are intentionally engineering their worldviews into these systems.

The Illusion of Objectivity

For all their innovation and technological wizardry, AI language models suffer from a centuries-old problem. Organizing and presenting information is fundamentally a projection of a worldview, not an attempt to perfectly reflect reality. Whether it’s the deliberate distortions of a map, the classification biases of a library, or the ideological prompts of a chatbot, human influence is inescapable. The danger of AI today isn’t some far-off future where machines take over; the danger is here and now, hiding in the illusion that these systems are objective and free from the very biases they were designed to reflect.

For users, understanding whose worldview these models represent is just as important as knowing who draws the lines on a map. AI is a powerful tool, but its responses are not an absolute truth. They are a singular perspective from an “indefinitely large number of responses” that might be produced. We must resist the fantasy of objective AI and begin the work of understanding the human biases that are, and always will be, at its core.