For generations, the name Edvard Munch has been instantly synonymous with a singular, primal image: the solitary, wailing figure silhouetted against a blood-red fjord in The Scream. This enduring masterpiece has fixed the Norwegian Expressionist in the popular imagination as the tortured master of angst, loneliness, and psychological isolation. A groundbreaking new exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in London, however, seeks to dismantle this one-dimensional myth. Entitled Edvard Munch Portraits, the show shifts focus entirely to the artist’s prolific and diverse work as a portraitist, revealing him not as a recluse, but as an intensely observant, cosmopolitan figure embedded within a dynamic European network of family, friends, and patrons. Spanning Munch’s entire career—from his early, brooding family studies to the powerful, often brutal psychological dissections of industrialists and bohemians—this exhibition compels us to look beyond the shriek of the famous figure and discover the man who, in his own words, could see “behind everyone’s mask.”

The Myth of the Solitary Artist

The conventional view of Edvard Munch is almost exclusively filtered through the lens of his most famous works, paintings like The Scream (1893) and Melancholy (1891), which are visual epics of despair and solitude. These pictures depict protagonists physically or emotionally separated from the world, cementing Munch’s legacy as the quintessential expressionist painter of human misery. While this is certainly a powerful component of his genius, it is a limited and ultimately misleading representation of his life and career.

The London exhibition, curated by Alison Smith, positions the work differently, defining Munch’s portraiture as any piece created “from a particular person in the moment.” By compiling this extensive body of work, the show argues that the artist was, contrary to popular belief, surrounded by people—a constant network that both supported and inspired him. His artistic journey was fueled by the intellectual and emotional connections he formed across Kristiania (now Oslo), Paris, and Berlin, proving him to be deeply engaged with his contemporaries rather than perpetually estranged from them. The resulting portraits serve as a rich, collective biography of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as interpreted by one of its most piercing psychological observers.

Roots of Expression: The Early Family Portraits

Before he fully developed the swirling, emotional intensity of Expressionism, Munch devoted his early efforts to painting his immediate family, a practice that documented a deeply challenging and artistically formative period. Munch’s childhood was marked by tragedy; he lost his mother and his elder sister to tuberculosis before he was even a young man, losses that undoubtedly fed the melancholy in his later, more famous pieces. The portraits from this era, however, offer a more complex study in artistic progress than mere grief.

These works are often characterized by a brooding, naturalistic realism that slowly began to evolve toward his mature style. His portrait of his Aunt Karen, for instance, shows a figure in black, her eyes cast down in what reads as quiet sorrow, capturing the subdued atmosphere of loss in the household. Another notable early work, Evening (1888), depicts his sister Laura gazing out across a grassy field. In this piece, one can witness the very moment his Expressionist tendencies began to coalesce: the canvas shows the influence of French artists and even, according to the curator, the influence of Japanese art through the unconventional framing and “squeezing” of Laura to the side. Most significantly, her blank, vacant stare anticipates the emotional vacancy that would later define his iconic works like Melancholy, revealing his family sitters as the vital subjects who helped him define his revolutionary aesthetic language.

Seeing Behind the Mask: The Bohemian Circle

As Munch moved beyond the constraints of his family home and traveled across Europe, his portraiture expanded to capture the vibrant, often chaotic, intellectual currents of the bohemian circles he joined in the great cultural capitals. It was here that his stated goal of seeing “behind everyone’s mask” truly came into its own, resulting in uncompromising and often controversial psychological studies of his friends and artistic rivals.

The exhibition includes figures like the writer and anarchist Hans Jaeger, a key figure in the Oslo bohemians who influenced Munch’s concept of the “Frieze of Life,” and the artist Karl Jensen-Hjell. Munch’s 1885 depiction of Jensen-Hjell, which features what was described as a “rakish, condescending air,” provoked outright outrage upon its initial display. This capacity to capture an unflattering truth about his subjects—the secret or hidden self—was central to his artistic vision. These portraits served as more than mere records of appearance; they were radical, emotional x-rays of the internal life of the fin-de-siècle intellectual, highlighting the tensions, egos, and psychological dramas that played out in the cafes and studios of his generation. Through this network of friendships, Munch established himself as a keen chronicler of the European avant-garde.

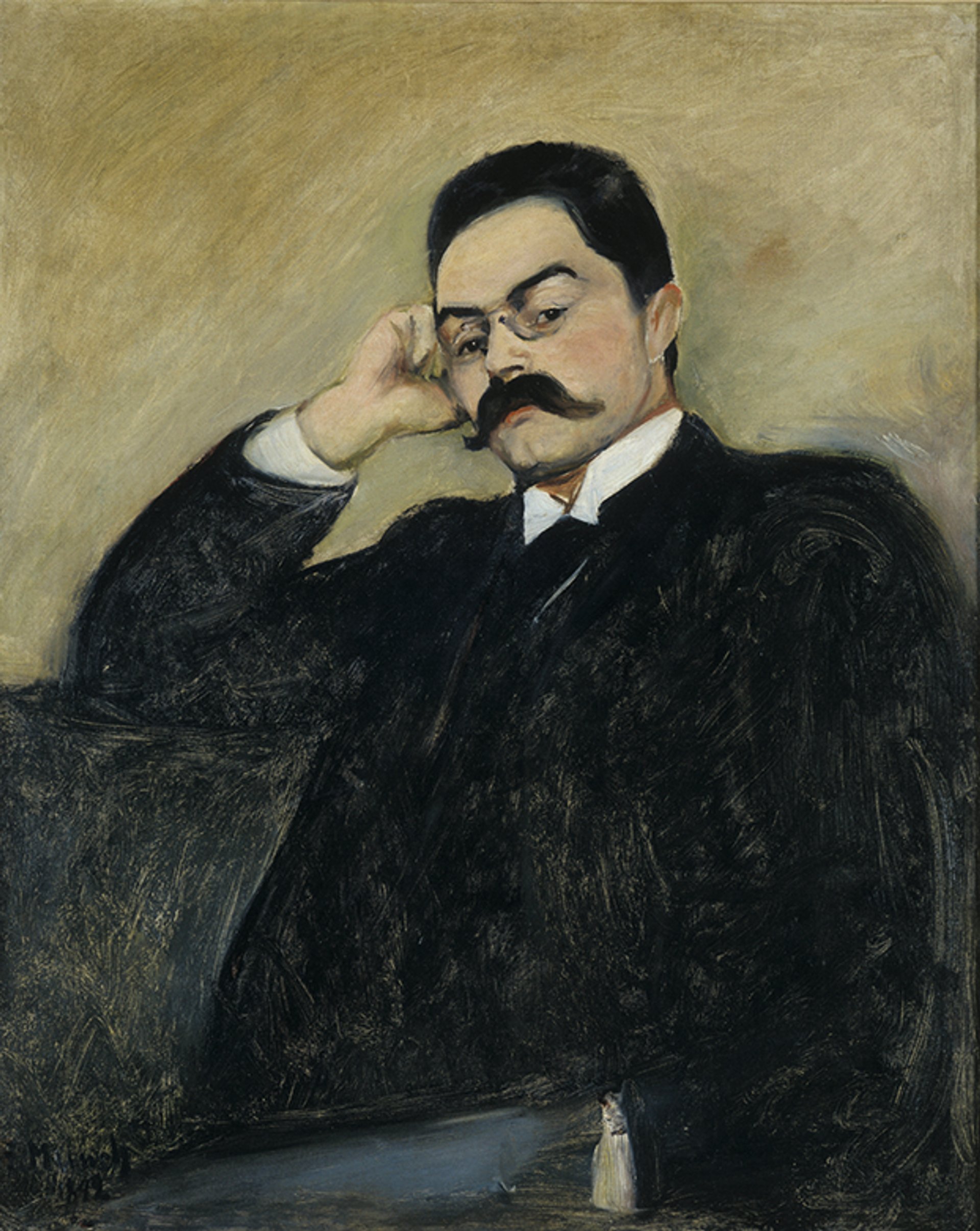

Patrons and the Psychology of Power

By the early 20th century, Munch had achieved significant European acclaim, and his portrait commissions began to reflect this commercial success. He was no longer just painting struggling artists; he was sought after by the newly powerful class of industrialists and professionals. Far from becoming a conventional society painter, however, Munch infused these commissions with the same psychological intensity he brought to his friends, often surprising his wealthy patrons with the starkness of their painted selves.

A spectacular example is his 1907 depiction of the powerful industrialist Walther Rathenau. The portrait is a dramatic vertical canvas, dominated by Rathenau’s imposing figure, one hand confidently clutching a cigar and his shoes gleaming—a bold visualization of capitalist power. Yet, the psychological depth was so acute that it reportedly startled the subject, who commented, “That’s what you get for having your portrait done by a great artist—you look more like yourself than you really are.” Rathenau’s reaction speaks volumes about Munch’s unique talent: he did not flatter, but instead revealed the underlying ambition, tension, or character that his sitter might have preferred to keep hidden. Even the psychiatrist who treated Munch, Daniel Jacobson, appears in the exhibition, proving that the painter’s intense gaze spared no one, including those in his most personal circle.

The Inner World of the Self-Portrait

Complementing the portraits of others are the selection of self-portraits featured in the exhibition, works that Munch used as relentless tools for self-analysis and exploration of his own character. The self-portrait was a lifelong genre for the artist, allowing him to experiment with technique and probe the shifting landscape of his health, mood, and identity across decades. These works reinforce the idea that Munch’s fascination with the “hidden self” was initially and continually directed inward.

This theme of the ‘hidden self’ extends to the more subtle symbolic elements woven into the portraits of his friends. For example, in his 1892 picture of the lawyer Thor Lütken, Munch concealed a miniature, brightly painted landscape on the sleeve of the sitter’s coat, a tiny scene featuring two embracing figures. This “hidden hug” is a compelling example of how Munch would sometimes use the portrait’s surface to suggest an unseen narrative or subconscious desire—a belief rooted, as curator Smith suggests, in a broader “fascination with the supernatural and the idea of everyone having a hidden self.” It also links to Munch’s deep personal attachment to his creations; he famously viewed his paintings as “his children,” often creating a second version he would photograph himself beside and find difficult to part with.

A Cosmopolitan Legacy

Ultimately, Edvard Munch Portraits succeeds in repositioning the Norwegian master beyond the familiar, brooding figure on the bridge. The exhibition places him firmly within his context, celebrating the rich and varied cast of characters—from family members and bohemian figures to prominent industrialists and key professionals—who not only financed his work but provided him with inspiration and vital companionship throughout his long career.

The collection illustrates a painter whose work was fundamentally shaped by his global experiences, from the domestic tragedy of his childhood home to the intellectual ferment of Paris and the commercial pressures of Berlin. The show reveals a prolific, canny, and ultimately connected man who was part of a “wonderful European network.” By celebrating these sitters as much as the artist himself, the National Portrait Gallery confirms Munch’s status as a master portraitist of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, one who used the human face to reflect not just individual anxiety, but the profound psychological complexity of the modern, cosmopolitan age. The exhibition, which runs from 13 March to 15 June, offers an essential and profound re-evaluation of one of history’s most influential artists.