The term “art collector” is often cloaked in an air of mystery and exclusivity, reserved by the art-world cognoscenti for those possessing an ill-defined “eye” or “sensibility.” Many art buyers, conscious of this lofty title, struggle with imposter syndrome, humbly protesting that they are merely “buyers,” not “collectors,” even as they pose in front of their prized possessions. However, the experience of commissioning an artist for the first time offers a profound rite of passage that shifts the focus from an exclusive title to a genuine engagement with the creative process. Novelist Chibundu Onuzo’s decision to commission a piece from young artist Antonia Caicedo Holguin—a choice driven by a desire to support her burgeoning talent and acquire a work that fit her specific home dimensions—proved to be an education in patronage. This singular experience revealed that true collecting is not about wealth or status, but about trusting and sustaining the artist’s vision, even when the final result defies all personal expectations.

The Elusive Gatekeepers of the “Real Collector” Title

The art world has long cultivated a system of exclusivity around the title of “collector,” a term which implies a level of knowledge and taste far beyond the simple act of purchasing a painting. According to the cognoscenti—often represented by fashionable gallerists—there is a distinct chasm between someone who merely buys art and someone who collects it. When pressed to define this difference, the explanations often dissolve into mysterious abstractions, referring to an “eye” or a “certain je ne sais quois,” ultimately establishing that a collector is simply whoever the established art community deems worthy.

This arbitrary and lofty standard explains why so many individuals who genuinely love and acquire art confess to feeling “imposter syndrome.” They may possess valuable works, but they hesitate to use the title for fear of being judged by these invisible rules of taste and sensibility. This dynamic means that many patrons approach the act of collecting with a defensiveness, focusing on acquisition rather than collaboration. It was into this charged atmosphere that the author made her own leap toward that coveted status, not by purchasing a million-dollar masterpiece, but by initiating a direct, working relationship with an emerging talent, a move that proved far more instructive than any gallery lecture.

The author’s journey into commissioning was born out of a blend of admiration and necessity. Having discovered Antonia Caicedo Holguin on Instagram, she was drawn to the young artist’s expressive style. After seeing the piece she wanted at a graduate show—a painting that marked a huge breakthrough in Holguin’s practice—she was faced with the trivial but undeniable obstacle of domestic architecture: the painting was too large to fit in her home. Knowing that she wanted to live with the art she bought, rather than locking it away in storage, she devised a “radical solution”: commissioning a new piece scaled specifically to her wall space. This practical decision marked the true beginning of her collecting journey, driven by the constraints of a real life, not the unlimited budgets of a grand patron.

Witnessing the Artist’s Great Leap Forward

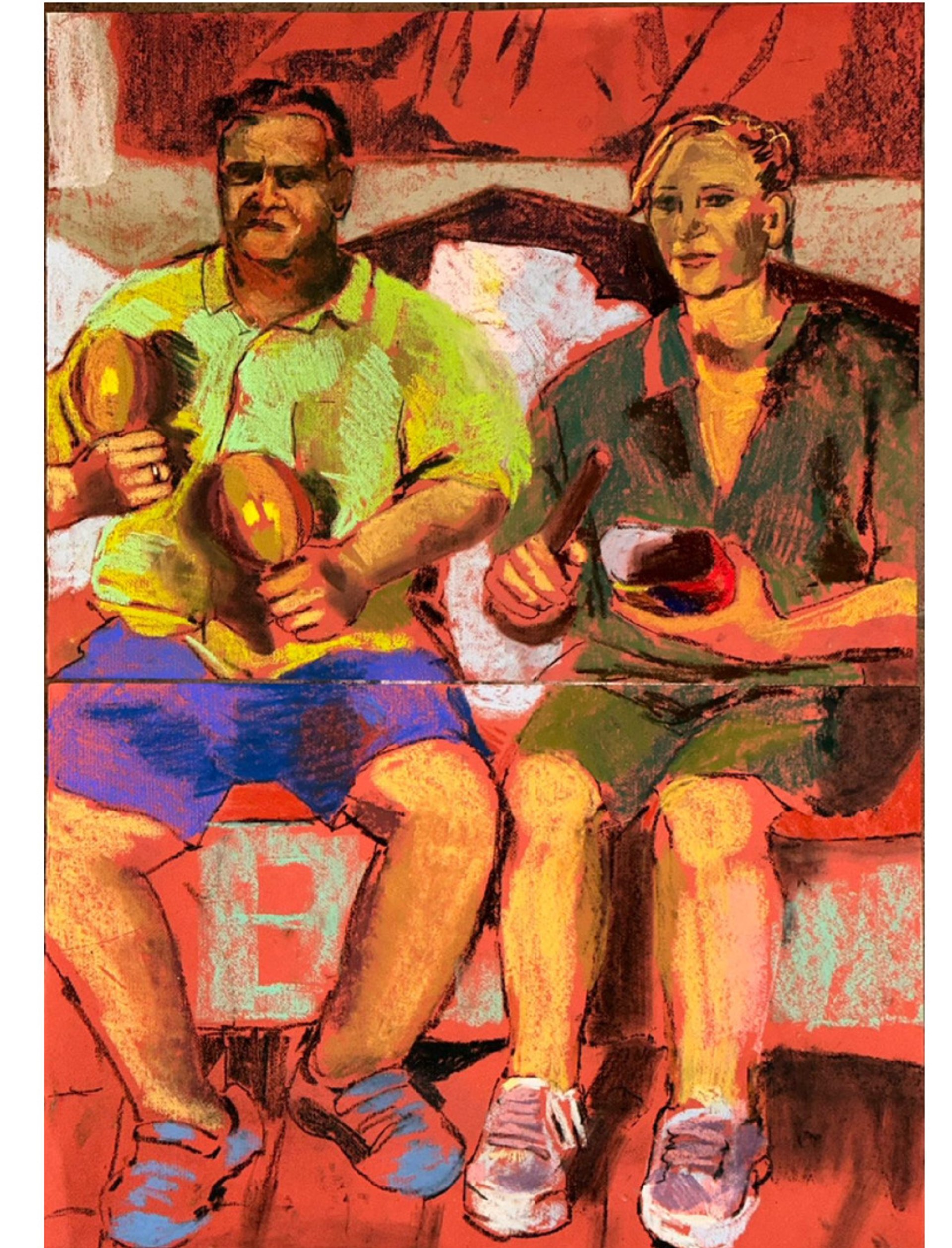

The initial connection with Antonia Caicedo Holguin happened organically, rooted in the author’s genuine appreciation for the artist’s burgeoning talent. Holguin, a graduate student at the Slade, initially worked in pastel on paper, creating portraits of friends and family that elevated mundane moments—such as a subject wearing headphones or working intently on a laptop—into romantic, expressive vignettes through sophisticated use of color and form. The author was initially drawn to these smaller pieces, even purchasing one titled Studio Shoes.

A subsequent studio visit revealed the challenges Holguin was facing in her practice. While she had larger canvases, the artist admitted that she was actively struggling to transfer the expressive freedom she achieved on paper to the scale of the large canvas, resulting in works that felt somewhat “constrained.” The author’s decision to wait and observe the artist’s development before committing to a major purchase was an act of informed patronage. It was a recognition that the best way to support an artist is not just to buy what they currently produce, but to invest in their trajectory and belief in their potential for growth.

That belief was validated a month later at the Slade graduate show. Holguin had successfully achieved her goal, presenting a work on canvas that perfectly translated her loose, expressive style to a grand scale. This rapid advancement demonstrated not just talent, but the capacity for decisive artistic progress—a quality that makes an artist truly exciting to collect. Since the breakthrough piece itself was physically too large to accommodate, the author felt entirely justified in moving forward with the commission, confident that Holguin was ready for the challenge. This demonstrated that the most fulfilling collection is often built on supporting artists at pivotal moments of their creative evolution.

The Intimacy and Impersonality of the Commission Process

With the decision made, the collaboration began, and the terms of the commission were deliberately kept loose. The author provided the dimensions of the required wall space, a necessary constraint, and asked for a painting featuring a group of characters, a theme Holguin was already exploring. At the close of the meeting, the artist posed a casual but pivotal question: “Do you and your husband want to be in the painting? Since there’s going to be multiple people in the piece, I can slot you in somewhere.”

For the author, this was the “siren song of vanity.” While not claiming to be a “grand patron of the arts” like those who commissioned the great masters, the idea of being immortalized in a Holguin tableau—even as a small element of a larger composition—was impossible to resist. The husband and wife agreed, securing their small, hoped-for place in a potential work of art history. This set the stage for the most revealing part of the process: the sketching session.

When Holguin arrived at their home the following Saturday to create pastel sketches, the mood immediately shifted. The author, feeling suddenly self-conscious, struggled to find an appropriate pose, cycling through mental images of grandiose art-historical postures: a heroic pose with hands akimbo or, more absurdly, a military pose seated on a rearing stallion. She settled for a comparatively humble pose, seated in an armchair with a book. What struck her most during the sketching, however, was not her own discomfort, but the artist’s gaze. Holguin looked at the couple with an intensity that was also completely “impersonal”—a clinical, objective assessment, as if they were “two blocks of marble, or two trees.” This momentary detachment allowed the author to grasp a critical insight: for the artist, the subject is not a friend or a patron, but a technical problem to be solved and a form to be captured with objective truth.

The Artist’s Prerogative: A Stunning Surprise

Following the initial sketches, a month of silence ensued while Holguin worked on the large canvas. This waiting period is a natural part of commissioning, a necessary surrender of control that differentiates it from the instantaneous gratification of purchasing a finished piece. When the author finally drove back to the studio to see the completed work, Holguin’s opening comment foreshadowed a surprise: “It’s a little bit different from what we agreed. But I felt I had to do what was right for the canvas.”

This statement was the purest assertion of artistic integrity. It immediately suggested that the author and her husband might have been “axed” from the composition entirely for the sake of the overall aesthetic. The reality, however, was the exact opposite, proving that the artist’s vision is often bolder than the patron’s request. Upon seeing the painting, the author’s intelligent critiques vanished, replaced by a simple, startled exclamation: “We’re so big!” Instead of being “slotted in somewhere” as minor characters, the author and her husband were positioned as the dominant figures, filling most of the canvas. The painting possessed the artist’s signature vigor and sophisticated color treatment, but the sheer prominence of their likeness was a genuine shock.

It was in the moments immediately following the reveal that the essence of patronage was defined. When Holguin nervously asked if she liked the piece, the author quickly affirmed, “It’s amazing.” Even more telling was the firm rejection of the artist’s nervous follow-up offer to “try and change it.” The author had to immediately protect the work’s integrity, recognizing that the artist had prioritized the demands of the canvas—the necessity of the composition—over the client’s presumed preference for a cameo role. This moment of surprise and subsequent validation was the final, and most profound, step in the education of a patron.

Patronage Beyond Acquisition: The True Meaning of Collecting

The experience of commissioning a work, ultimately, bestowed upon the author something far more valuable than the elusive title of “collector.” It granted a unique, first-hand insight into the very nature of creation, a process that had remained opaque during her previous years of merely buying existing art. The collector who buys only completed works sees the result; the collector who commissions witnesses the journey—the struggle, the objective gaze, the unexpected leap of faith, and the final, necessary divergence from the initial brief.

This collaboration creates a shared history between the patron and the artist. The finished piece, which now hangs proudly in the author’s living room, is not just an object; it is a monument to a specific, challenging, and revelatory interaction. It is a record of the artist’s breakthrough, the patron’s vulnerability during the sketching session, and the final, mutual respect when the artistic vision was asserted over client expectation. The work’s success is therefore an acknowledgment of the artist’s talent and the patron’s wisdom in supporting that talent without smothering it.

For anyone considering a first commission, the takeaway is clear: it is a one-of-a-kind, personal experience, especially when supporting an artist whose work you deeply admire. It is an act of genuine patronage that sustains the art world at its most fundamental level. The final work will be unique, infused with the history of the collaboration. And while the result may not be what was initially expected, as long as the artist remains true to their own vision, the work will be amazing, reinforcing the ultimate truth that the best collecting is an act of trust.