Along the sun-drenched coast of Italy, situated between Rome and Naples, lies the town of Sperlonga, home to one of the most remarkable archaeological discoveries of the 20th century. Here, in the ruins of a sprawling seaside villa once owned by the paranoid Emperor Tiberius, lies a vast natural grotto that was transformed into a dramatic, open-air dining hall. This “spelunca” was not merely a luxurious retreat; it was an imperial stage for colossal marble sculptures that brought the tumultuous, tragic myths of Homer’s Odysseus to breathtaking life. The entire tableau was shattered in 26 AD when the cavern roof catastrophically collapsed, a disaster that historians recorded and that inadvertently sealed the sculptures in time. Recovered as over 7,000 fragments in 1957, these monumental artworks—including the terrifying Scylla group—offer a unique, visceral glimpse into the opulent artistic tastes of the Julio-Claudian dynasty and stand as a defining example of Hellenistic art in the Roman world.

The Imperial Stage: Tiberius’s Seaside Retreat

The complex known today as the Villa of Tiberius began as a simpler Republican-era structure but was massively expanded by the emperor to serve as his preferred coastal getaway. Spanning over 300 meters along the Tyrrhenian shore, the villa complex included residential quarters, thermal baths, water reservoirs, and private moorings. The crowning feature, however, was the large natural grotto, or spelunca, which Tiberius ingeniously incorporated into the villa’s design as a lavish and highly theatrical space for hosting banquets.

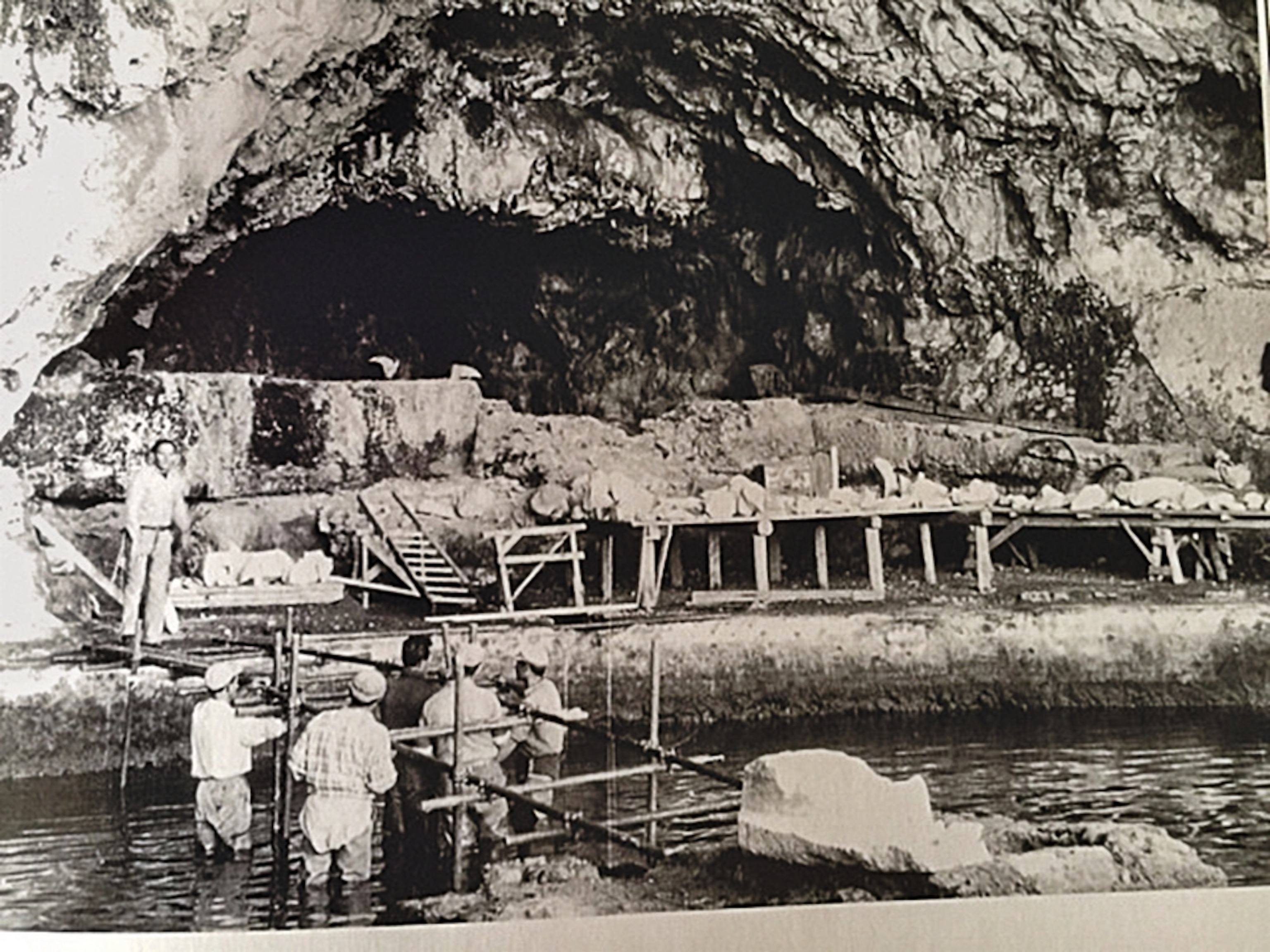

The cavern was architecturally modified to maximize its dramatic potential. At the grotto’s mouth, a large, rectangular sea-fed pool was constructed, connecting to an internal, artificial circular pool that occupied the majority of the grotto’s floor. This internal pool was designed to hold prized fish, making it a spectacular piscina for both aquaculture and entertainment. At the center of the circular pool, a small, square island was built to house the triclinium—a dining space furnished with couches—allowing the imperial party to dine literally suspended over the water, surrounded by the cool air, natural rock encrustations, and the spectacular statuary. This entire setting, complete with artificial waterfalls and colored opus sectile flooring, created an atmosphere of unparalleled luxury and mythological immersion that was unlike any other imperial residence.

Homer’s Heroes: The Colossal Sculpture Program

The true heart of the Sperlonga Grotto lay in its extraordinary sculptural program, a narrative masterpiece that brought the epic journeys of the Greek hero Odysseus (Ulysses) into a tangible, high-drama reality. Four main colossal marble groups, all in the evocative, highly expressive Hellenistic Baroque style, were strategically placed around the pool and grotto interior. The central focus was the magnificent Scylla Group, which depicted the ferocious sea monster, whose body sprouted wolf-like heads and tentacles, violently attacking Odysseus’s ship. This fragmented, multi-figure tableau was set in the main pool, creating the terrifying illusion that the monstrous assault was actively unfolding around the diners.

To the rear of the cave, dominating the space, was the Blinding of Polyphemus group. This harrowing scene showed Odysseus and his crew driving a stake into the eye of the enormous, drunken Cyclops, their heroics framed against the dark backdrop of the natural cavern wall. The collection was completed by two other major groups: Odysseus carrying the body of Achilles (often identified with the famous Pasquino group motif of a warrior supporting a fallen comrade) and The Theft of the Palladium (a key episode from the Trojan War). The choice of the Odyssey theme—a tale of struggle, cunning, and eventual triumph over adversity—was a deliberate reflection of imperial power, subtly linking the Emperor’s own fate and perseverance to the epic hero.

The Rhodian Masters and a Question of Genius

The creators of the Sperlonga sculptures are almost as legendary as the heroes they carved. An inscription found on the stern of the Scylla ship fragment names three artists: Agesander, Athenodoros, and Polydoros, confirming their Rhodian origin. This discovery ignited one of the greatest debates in art history, as the Roman historian Pliny the Elder attributed the magnificent Laocoön Group—a pivotal work in Western art—to the very same three Rhodian sculptors.

The sculptures at Sperlonga, characterized by their high drama, muscular forms, and baroque theatrics, undoubtedly share a stylistic lineage with the Laocoön. However, the Sperlonga pieces show an exceptionally extensive use of uncarved marble struts to strengthen the figures, a technique suggesting the works may have been crafted off-site, possibly in Rhodes, and braced for transport. While some scholars argue the Sperlonga sculptures are earlier works by the same artists, others suggest they might be sophisticated Roman-era commissions executed by descendants of the original Rhodian workshop. Regardless of the exact chronology, the Sperlonga Grotto became the single most important trove of Hellenistic monumental sculpture found in a Roman imperial context, a crucial artistic link between the height of Greek expression and the tastes of the Roman Empire.

The Day the Grotto Fell: History Encased in Stone

The life of the Sperlonga Grotto as an imperial dining hall came to an abrupt, violent, and historically significant end in 26 AD. The event is recorded in chilling detail by the Roman historians Tacitus and Suetonius. While Tiberius was hosting a lavish feast in the grotto, portions of the roof suddenly gave way, raining large chunks of the coastal cliff down upon the dining party. The collapse instantly killed several attendants and nearly crushed the emperor himself.

Tiberius’s life was saved only by the swift, heroic actions of his powerful and ambitious confidant, Lucius Aelius Sejanus. According to the accounts, Sejanus threw himself over the emperor, taking the brunt of the falling debris. This act of loyalty and bravery secured Sejanus’s position as the emperor’s most trusted advisor, cementing his rise to political dominance within the Roman state. The near-fatal incident had profound political repercussions, but for the grotto, it meant immediate abandonment. The shattered sculptures and the ruined dining hall were left untouched, effectively preserving the fragments in a geological tomb until their eventual rediscovery nearly two millennia later.

From Fragments to Masterpiece: The Archaeological Triumph

The spectacular site was rediscovered purely by accident in 1957, when civil engineers constructing the modern coastal road, the Via Flacca, stumbled upon large quantities of broken marble. Subsequent excavations yielded an astonishing haul: over 7,000 fragments of colossal marble sculpture, all mixed with the debris of the collapsed cave roof. Archaeologists faced the monumental task of piecing together this gigantic, three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle.

The identification of the sculpture themes was aided by the discovery of an inscription—a short piece of poetry by the otherwise unknown Frontinus—that explicitly praised the beauty of the grotto and mentioned the statues of Scylla and the blinding of the Cyclops by Odysseus. Relying on this crucial text and painstaking reconstruction, experts were able to reassemble the main groups, including the awe-inspiring Scylla group. Today, these carefully reconstructed masterpieces are the centerpiece of the National Archaeological Museum of Sperlonga, built specifically on the villa grounds in 1963. The museum not only houses the original fragments and reconstructions but also integrates the villa and grotto ruins into the visitor experience, creating a singular destination where the drama of art, history, and mythology converge.