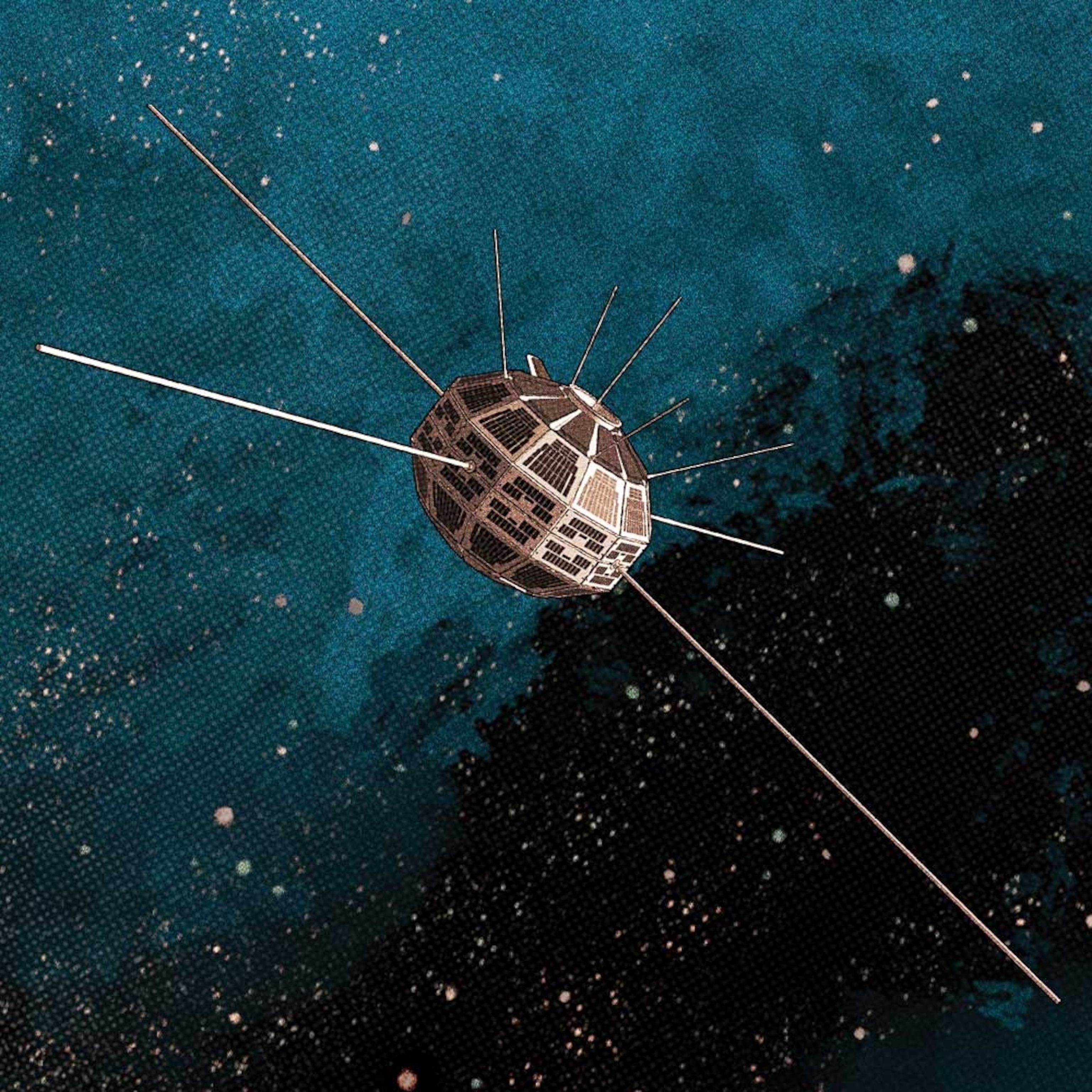

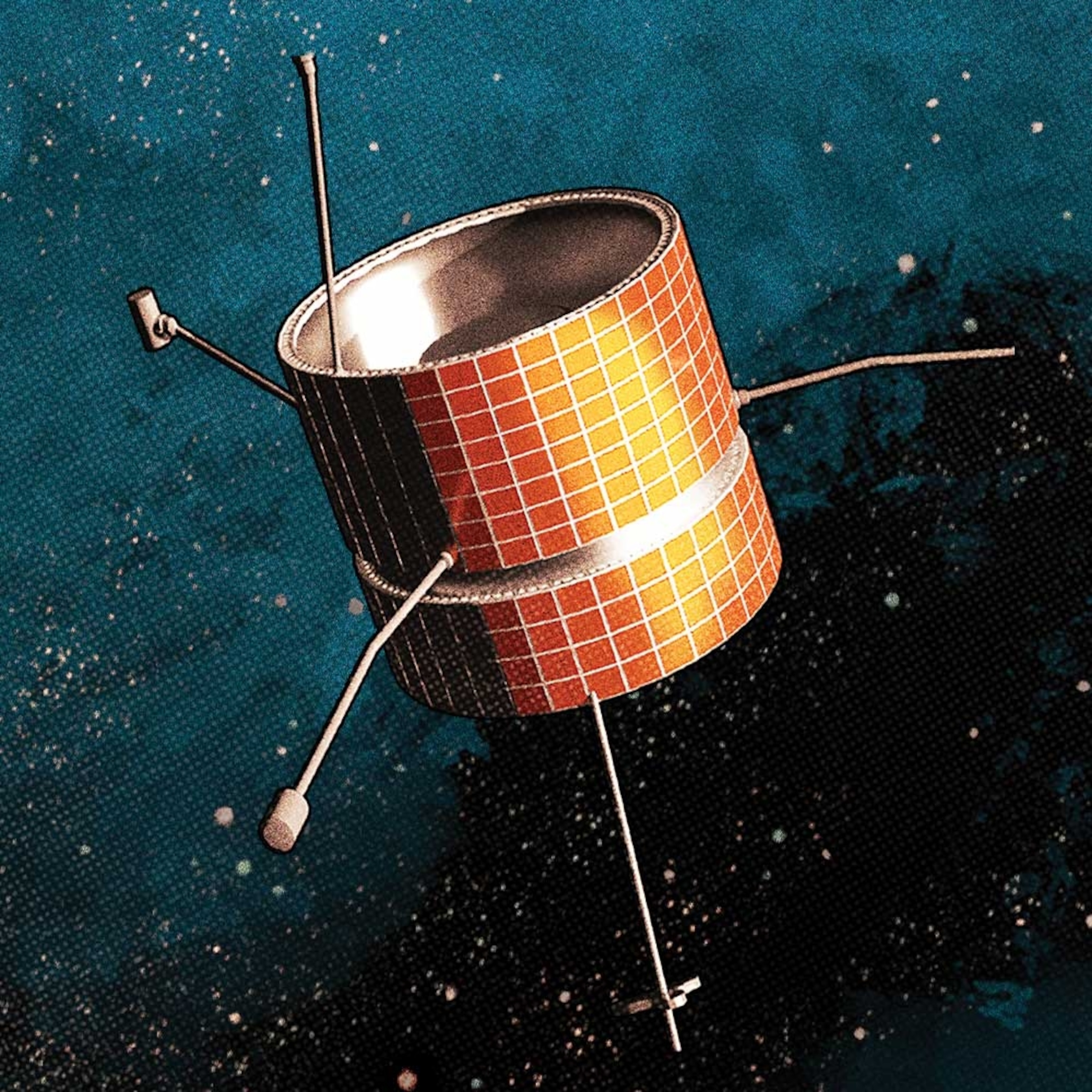

In the vast, inky blackness of low Earth orbit, an antennaed aluminum ball silently circles our planet, a ghost of the Cold War’s beginning. Known as Vanguard 1, this defunct satellite is, in one view, nothing more than a glorified piece of space junk—a “grapefruit,” as Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev once mockingly called it. Yet, to a growing coalition of engineers and historians, it is an invaluable artifact of the early space age, a “precious object” ripe for retrieval. A long-shot plan to bring this and other pioneering satellites home is sparking a profound debate, forcing us to ask: What is space junk, and what is space treasure? This conversation challenges our notions of preservation, raises complex questions of ownership, and highlights the urgent need to define a new kind of heritage in an increasingly crowded orbital environment.

The Case for Retrieval: Junk or Treasure?

The argument for retrieving our oldest space relics is rooted in a dual belief: that they possess immense historical and scientific value, and that their removal is a proactive step toward managing space debris. Matt Bille, a space historian and a proponent of the idea, frames Vanguard 1 not as a derelict object but as a potential goldmine of data. By bringing the satellite back to Earth, scientists could analyze its materials to understand the long-term effects of exposure to the extreme conditions of space—a valuable insight for future missions. The physical presence of the object, he argues, would also allow for a richer, more tangible connection to the past, deserving of a place in a museum like the Smithsonian.

Beyond the historical and scientific merit, proponents of retrieval also point to the increasingly crowded nature of low Earth orbit. With more than 14,000 satellites currently in orbit, and countless pieces of debris, the risk of collision is a growing concern. While bringing back a single satellite won’t solve the entire problem, the hypothetical missions designed to retrieve them could serve as a powerful proof of concept for future technologies aimed at actively clearing space junk. This perspective casts retrieval as a forward-looking, pragmatic solution that honors the past while safeguarding the future.

The Ethos of Preservation: A Different View

Not everyone in the burgeoning field of space archaeology agrees with the retrieval plan. Alice Gorman, a leading voice in the discipline, argues that these historic objects should be left where they are. This “in situ preservation” approach is based on the idea that an artifact’s value is intrinsically tied to its original context. To Gorman, the satellites, in their orbital home, are part of a larger historical landscape. They are a physical record of humanity’s initial forays into the cosmos, and removing them would be akin to taking a priceless relic from an archaeological site. She also notes that remote sensing methods, such as photography and other technologies, can be used to study them without the risks and costs of a physical mission.

This perspective also brings to light the complex ethical and political questions that a retrieval mission would raise. Who decides which relics are “precious” enough to be brought back? Who would own these artifacts after they are retrieved? The idea of a private robotics company or a single nation claiming ownership of an object that belongs to the shared history of humanity is a contentious one. The in situ argument suggests that these objects are safer in orbit, where they belong to no one nation and serve as a symbol of our collective history, a powerful reminder of our first steps into the final frontier.

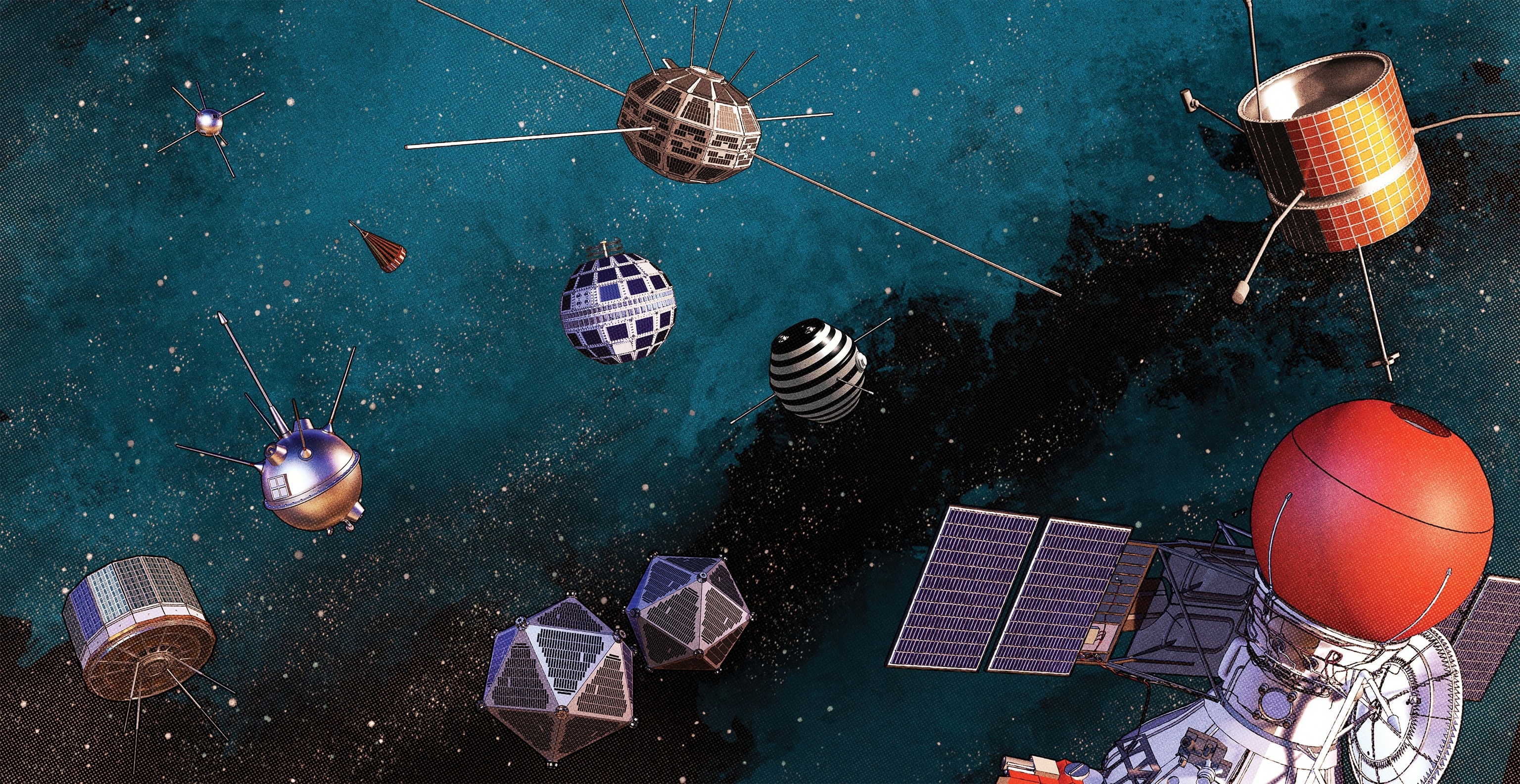

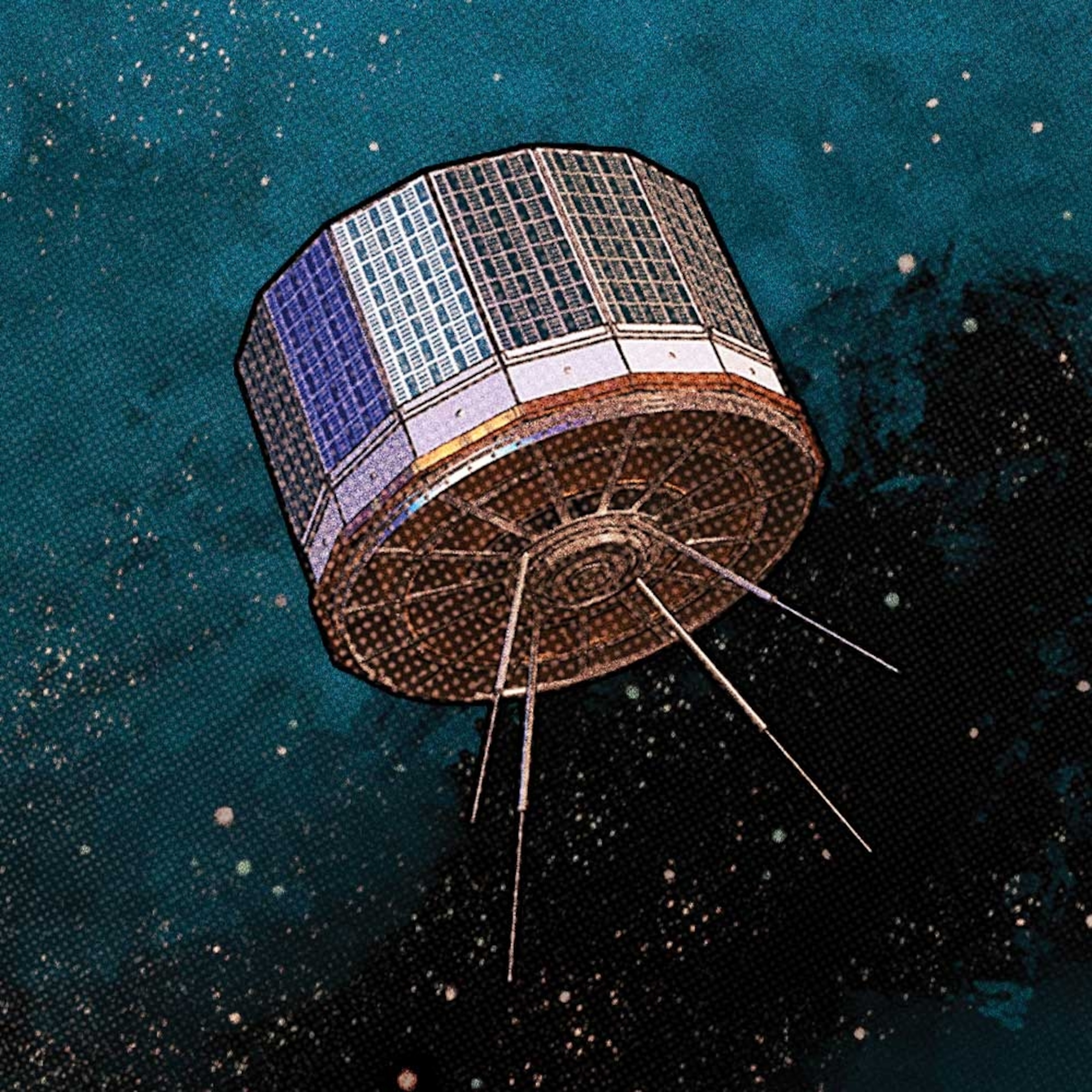

A Pantheon of Pioneers: The Candidates for Rescue

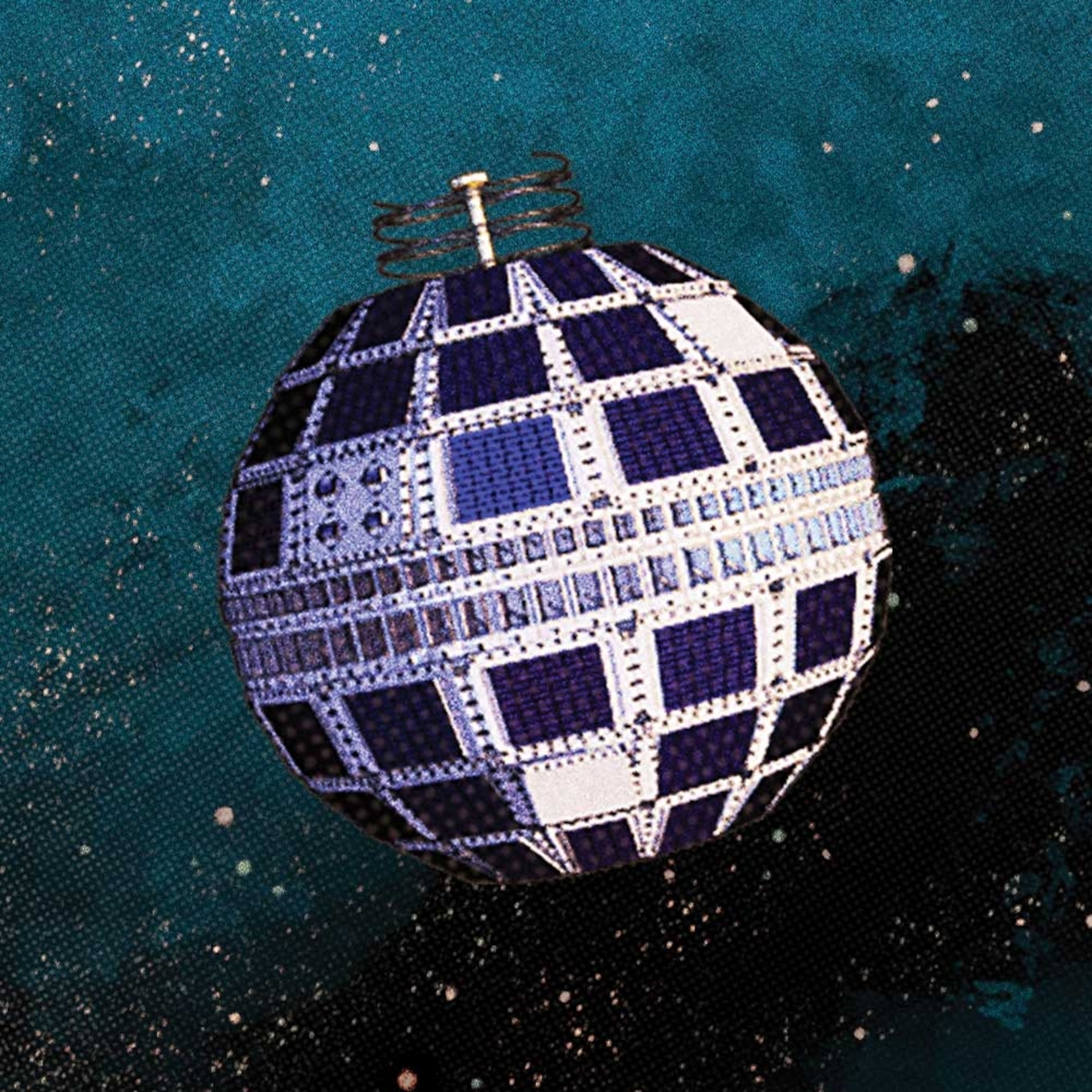

Beyond Vanguard 1, the proposal for retrieval has identified a list of other candidate satellites, each a pivotal piece of space history. They are not just defunct machines but pioneers that represent a new kind of human accomplishment. Luna 1 and Pioneer 4 were the first spacecraft to escape Earth’s gravity, setting a precedent for interplanetary travel. Tiros 1 and Alouette 1 established the foundation for modern weather forecasting and atmospheric science, paving the way for the satellites that now provide us with vital data every day. The debate also includes Telstar, the first active communications satellite, and Early Bird, the first commercial satellite in geostationary orbit, which laid the groundwork for modern global communications and cable television.

These candidates for rescue are more than just a list of names; they are a chronicle of our collective ambition. They include international collaborations like Vela 1A & B and Vega, which crossed Cold War lines to monitor nuclear activity and study Halley’s Comet, respectively. By focusing on these objects, the debate is reframed from a simple question of junk versus treasure to a more profound discussion about how we choose to define and honor our legacy in the cosmos. It forces us to confront the fact that our history is not just on Earth but is also orbiting silently above us, waiting for us to decide its fate.

The Path Forward: Defining the Future of Space Heritage

The debate over the oldest satellites in space is no longer just a hypothetical thought experiment. As orbital space becomes increasingly congested, the question of how we manage our technological legacy is becoming urgent. This conversation forces us to define a new framework for space heritage, one that balances the desire for preservation with the practical realities of a crowded environment. The future may involve a hybrid approach, where some artifacts are left in their orbital context for remote study, while others are carefully deorbited for scientific analysis or public display.

Ultimately, this debate is about more than just old satellites. It’s about how we view our place in the universe and how we choose to honor our past. It’s a powerful reminder that our first steps into space left a physical mark, and it is now our responsibility to decide what that mark means for future generations. The answer may lie not in a simple choice, but in a new, more nuanced understanding of what we leave behind and what we choose to bring home.