For most of us, the days of standardized testing are a distant memory. But for parents and students, the pressure to perform on cognitive ability tests, which are very similar to IQ tests, is a modern reality. Imagine a parent learning their child’s cognitive ability test (Cat) score is below average. Immediately, a cascade of unsettling questions arises: Will this prevent them from getting into a top university or securing a successful career? Amidst this anxiety, a hopeful thought might emerge. If test scores matter so much, can a person’s performance be improved through practice, just like any other skill? Science offers a clear answer: while you can certainly boost your score on these cognitive tests, the practice won’t actually make you more intelligent.

The Enduring Legacy of Standardized Testing

Standardized testing has a long and storied history in the world of education and professional selection. One of the most famous historical examples is the Chinese civil service examination, an exceptionally rigorous assessment established during the Sui dynasty (AD 581–618). Its purpose was to select the most capable candidates for a highly prestigious role in the imperial bureaucracy. This practice of using objective assessments to determine a person’s potential for success is still very much alive today.

In modern education, institutions around the world continue to test students on a variety of skills, including both foundational subject knowledge and broader cognitive abilities. The SATs in the United States, for instance, are widely used to filter applications for prestigious universities. While testing subject knowledge in areas like math and science seems logical—as it measures a student’s readiness to be a productive citizen—the role of cognitive testing is less obvious and often more controversial. However, it is seen as a valuable tool for predicting a person’s future academic and professional success.

Unlocking the Logic of Cognitive Abilities

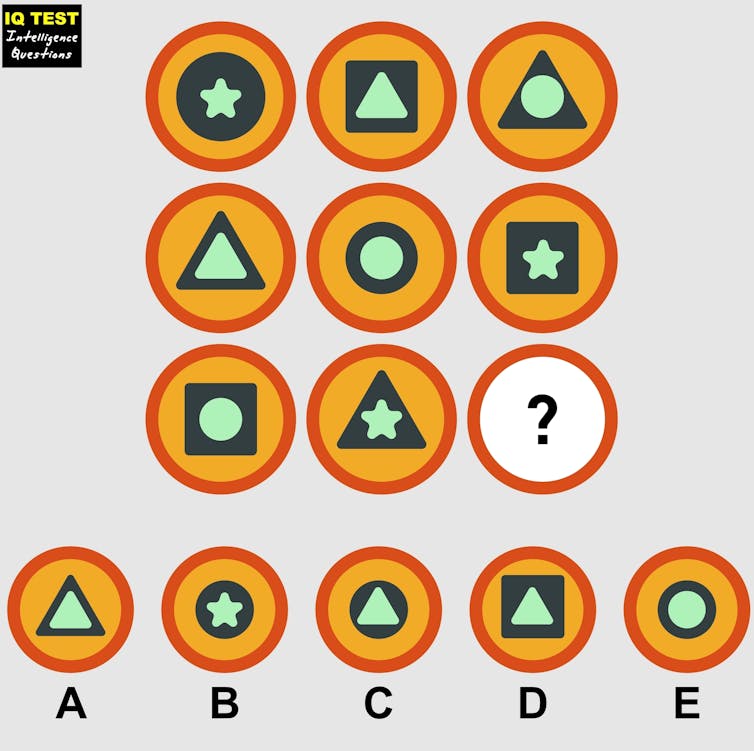

Cognitive tests are meticulously designed to measure a variety of intellectual capabilities rather than just acquired knowledge. The latest version of the Cat, for example, assesses four distinct areas of reasoning: verbal, nonverbal, quantitative, and spatial. The underlying principle is that a person who excels at one of these tasks is likely to do well on others, suggesting the existence of a general mental ability to solve unfamiliar intellectual problems. This fundamental ability is what we commonly refer to as intelligence.

A person’s score on a comprehensive cognitive test is often used as a proxy for their intelligence, commonly referred to as their IQ. Although a single number cannot capture the full complexity of a person’s mind, IQ scores have been shown to be the single best predictor of academic achievement and a significant predictor of professional success. For this reason, cognitive testing remains a fairly reliable way to predict a person’s potential for achieving real-life goals. The question then becomes whether this valuable predictive tool can be “gamed.”

The Practice Effect: A Boost for Scores, Not Smarts

The science is unambiguous on this point: performance on cognitive tests can be improved with practice. A good score on a cognitive test is a sign of intelligence, and being intelligent is a significant advantage in life. However, it is a crucial distinction to understand that this improvement does not equate to an increase in intelligence. For example, one study found that simply taking a common nonverbal reasoning test twice increased a person’s score by the equivalent of roughly eight IQ points. Similarly, several rounds of repeated testing can yield even larger gains, although a plateau is eventually to be expected.

This phenomenon is why standardized tests, such as those used by Mensa for their membership criteria, are not publicly available. If a person were to practice a test beforehand, the score would, to a certain extent, measure their expertise in performing the test rather than their innate intelligence. In this way, repeated practice can make the test results essentially un-interpretable as a measure of a person’s true intelligence. The score is a measure of how good you are at taking that specific test, not how intelligent you have become.

The Myth of Trainable Intelligence

For decades, the idea of “training” intelligence has been a popular one, with countless brain-training apps and programs promising to enhance cognitive ability. However, scientific evidence consistently points in the opposite direction. While people who train on a specific cognitive task consistently get better at that task (or very similar ones), this improvement does not transfer to other, unfamiliar cognitive tasks or academic subjects. This lack of transferability is the key piece of evidence supporting the claim that intelligence is untrainable.

This does not mean that practicing for tests like the Cat is without practical purpose. For parents, it can provide a useful way to prepare a child for an important school selection process and may even give them a confidence boost. However, it is vital for parents and students alike to recognize that while a test score can improve, a person’s underlying general mental ability remains unchanged.

Beyond the IQ Score: The True Keys to Success

While high intelligence is an undeniable advantage in life, it is by no means the sole determinant of success. The notion that a person’s fate is sealed by a single number on a cognitive test is a false one. Academic and professional skills, unlike innate intelligence, are highly trainable. Hard work, perseverance, social skills, personality traits, and even luck often have a profound and lasting effect on an individual’s life and career path. A person who may not have the highest IQ can still achieve remarkable things through determination, creativity, curiosity, and a positive attitude. In the end, a cognitive test score is just one piece of a much larger, and far more complex, puzzle.