Despite the recurring gridlock in Washington, D.C., that periodically triggers a federal government shutdown, the overwhelming consensus from major tour operators is that national park itineraries are proceeding with remarkably little disruption. While the closure of government agencies leads to the furlough of most National Park Service (NPS) staff—resulting in the shuttering of visitor centers, educational programs, and some essential services—tour companies have demonstrated extraordinary operational resilience. A combination of factors, including private concessions handling essential maintenance, proactive funding from state and local governments, and the nimble nature of organized, private tours, has allowed these businesses to uphold their commitments. This continuity, however, belies a serious underlying challenge: the loss of millions in park revenue, the burden placed on unpaid NPS workers and non-profit partners, and the environmental damage that results when vast public lands are left unmonitored.

Operational Continuity: The Tour Operator Advantage

One month into the federal government shutdown, a survey of leading tour companies, including the Globus family of brands, Tauck, and Intrepid Travel, reveals a notable absence of major itinerary changes or operational issues. This resilience stems from the unique structure of organized tour groups, which are self-contained and less reliant on federal services than independent travelers.

Tour operators have found that while most NPS staff are furloughed, the major roads, trails, and open-air memorials within parks generally remain accessible. Furthermore, a crucial element in maintaining functionality is the role of private concessionaires. Companies like Xanterra, which handle lodging, retail, and food services in many large parks, continue to operate, often maintaining basic sanitation and public restroom facilities that federal staff would normally manage. This private infrastructure serves as a vital buffer, ensuring that the fundamental components of the tour experience—transportation, accommodation, and food—remain in place, allowing organized travel groups to navigate the parks smoothly.

Filling the Service Gap: Private Tours and Interpretation

The absence of furloughed park rangers and the closure of visitor centers and interpretive exhibits have inadvertently highlighted the value proposition of organized tours. With no ranger-led programs or interpretive talks available, the role of the private tour guide becomes even more critical.

As noted by Intrepid Travel’s North America operations director, small-group travel is effectively filling the void in interpretive and educational services. The private tour guide, armed with extensive knowledge and local context, can transform a simple drive into a rich, informative experience, providing the essential context about the geology, ecology, and history of the park that guests would normally receive from NPS staff. In fact, some operators have reported an increase in demand for their specialized tours, suggesting that travelers are seeking organized experiences specifically to mitigate the confusion and lack of support they might face attempting to visit the parks independently during a shutdown.

The State and Local Lifeline: Funding Basic Operations

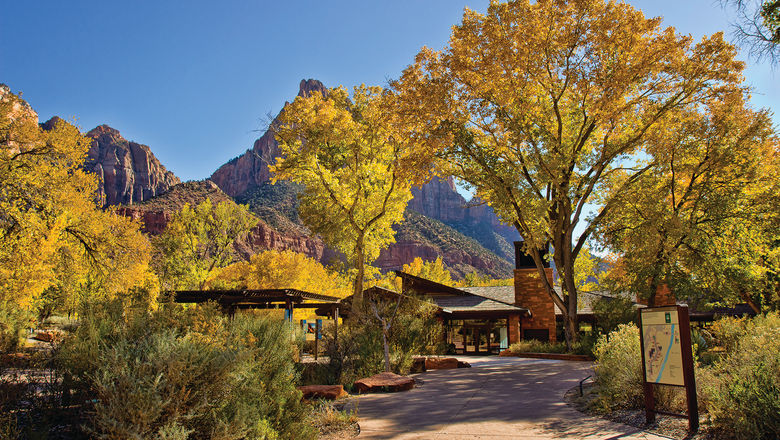

The operational continuity of many highly visited national parks is heavily subsidized during the shutdown by proactive measures taken by state and local governments. Nowhere is this more evident than in Utah, home to the “Mighty Five” national parks (Arches, Bryce Canyon, Canyonlands, Capitol Reef, and Zion).

The Utah Governor’s Office of Economic Opportunity has provided daily funding to keep visitor centers at all five of the state’s national parks staffed and open. This immediate injection of state funds has successfully prevented a drop in visitation at parks like Zion National Park, which has continued to see tens of thousands of visitors on fall weekends, a peak season for the area. This swift, tactical financial support is a recognition that the economic health of “gateway communities” near the parks—towns whose entire economies are built upon tourism revenue—cannot withstand the devastating impact of a full park closure. This localized effort has been crucial in preserving the visitor experience and maintaining local economic stability, though it relies on temporary, non-federal funds.

The Hidden Cost: Revenue Loss and Environmental Risks

While tour groups are maintaining their schedules, the government shutdown carries severe long-term costs that are not immediately visible to the tourist. The National Park Service loses millions of dollars in vital revenue every day the parks remain open but unstaffed at entrance gates. For Zion National Park alone, the estimated loss in uncollected entrance fees ranges from $35,000 to $50,000 per day. This money, 80% of which typically remains in the park for maintenance, conservation, and projects, is irrevocably lost, further exacerbating the NPS’s long-standing backlog of deferred maintenance.

The greatest risk, however, is the threat to the integrity of the natural resources themselves. Parks that remain open with minimal staffing face issues of overtourism without management. The resulting problems, documented in past shutdowns, include overflowing trash and unsanitary restroom facilities, which pose public health risks and can increase the potential for dangerous human-wildlife encounters. Conservation groups have voiced strong concern that the policy of keeping parks open with skeleton crews risks irreparable damage from littering, graffiti, and off-trail behavior, undermining the core mission of resource protection that the furloughed staff are dedicated to upholding.

Perception vs. Reality: The Impact on Gateways

The impact of the shutdown on tourism economies is proving to be a mixed bag, largely dependent on local management and public perception. Communities like those near Zion, which have benefited from proactive state funding and the smooth operations of tour groups, have seen visitor numbers hold steady. Conversely, some gateway communities, such as Big Sky, Montana, near Yellowstone National Park, have reported a decline in visitors.

Local tourism leaders attribute this decline to the public’s perception that the parks are closed, demonstrating the sensitivity of the travel consumer to negative news and uncertainty. This distinction underscores a key finding: while the physical reality of the parks may be accessible due to private and local efforts, the psychological barrier created by a federal shutdown can still deter independent travel, making the continued, organized operations of tour operators a vital component in preserving the flow of tourism dollars into fragile local economies.